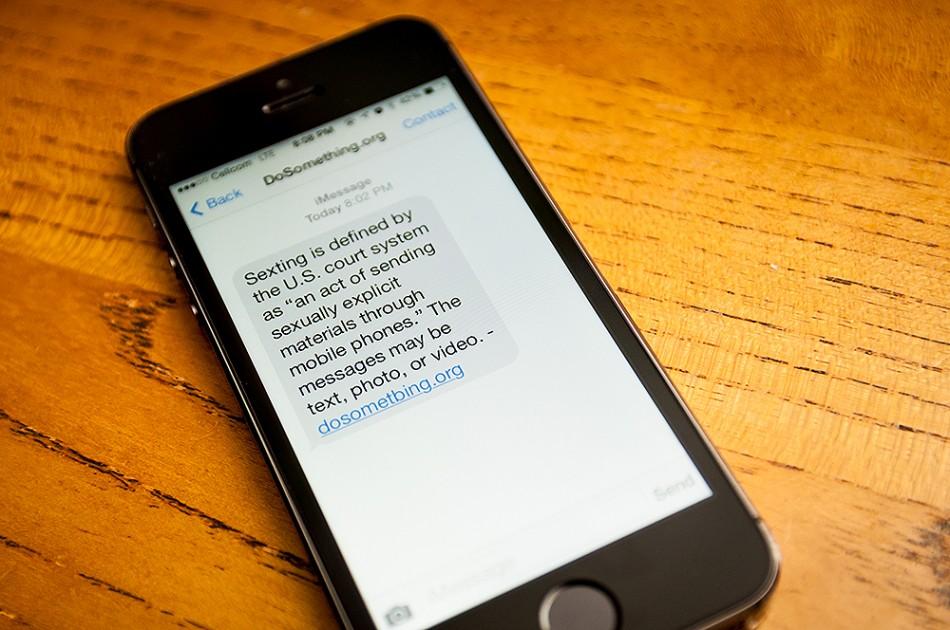

Miofsky studies reasons behind sexting

According to dosomething.org, 33 percent of college students have sent a nude photo to someone else.

Karin Miofsky, new assistant professor of criminal justice, has a doctorate in criminology and criminal justice and has a special interest in juvenile delinquency, particularly in the areas of bullying and sexting.

With the help of a few grants, Miofsky was able to delve into the complexities of sexting.

She was granted access to nine high schools, three in Massachusetts, three in South Carolina, and three in Ohio, where she held separate focus groups.

For example, on Monday, she would have a focus group of six-10 girls, and then on Tuesday, she would have a focus group of six-10 boys.

Her specific focus was on how youth define sexting, under what circumstances and motivations they engage in it and whether or not they are aware of the legal repercussions.

She asked the students if they ever sent, received or forwarded sexually explicit images or text messages.

In the end, she found that about 30 percent of youth sent some sort of sexting image or message and about 40 percent received an image or message. For the most part, the sexts were exchanged as part of a romantic relationship.

However, at the other end of the continuum, bullying comes into play with the malicious intent to harass, exploit, humiliate or extort individuals, which led Miofsky to explore the interconnectedness of those topics.

She found that sometimes youth were not even forwarding pictures of a boy or girl from school, but were instead downloading images from the internet and distributing them, while falsely claiming that they were pictures of a boy or a girl in the school.

The majority of the time, Miofsky discovered, the photos were being forwarded by a jilted ex as a means of humiliating the other person.

Miofsky also had the opportunity to interview parents, school educators and law enforcement individuals who worked within the schools.

For parents, the biggest concern was questioning what would happen to the photos exchanged after a youth relationship dissolved.

That precise issue, however, is being incorporated into many schools curriculum, specifically in the social development curriculum.

One thing Miofsky asked about was how schools should address the issue of sexting. Overall, she found that the students were simply not being engaged in discussion about the issue of sexting.

Administration decided not to resort to scare tactics, as the students were already engaging in the behavior and prevention was nearly impossible. Instead, the topic would be broached in the context of sexual development, healthy relationships and general discussion about the issue.

Miofsky found that it’s normal for youth to take these types of risks, make mistakes and learn from them, but overall they need to learn to effectively negotiate their social terrain, including their sexual development.

“The majority of the time the scenario is from peer pressure,” said Miofsky. “Boys were requesting a photo from the girls and the girls would send the photos to the boys. So most of the time we saw it was the girls sending the photos, even though the conversation was being initiated by the boy. So a lot of it had to do with pressure. You know, acceptance from girls, but also then increasing of status from boys.”

Miofsky blames the sexualization of culture and media for the pervasiveness of sexting.

“I think that as parents and educators we can talk to youth, but most of the time, what I’ve found is that their understanding of these kinds of topics come from the media, so I feel like there needs to be just a societal change,” said Miofsky. “We’re at a cultural shift in society right now that we need to think about.”

In addition, she also asked the students about consequences. She discovered that most of the consequences they mentioned were social consequences. Very few asked about consequences involving college and job applications or legal sanctions, which are very serious for anyone under the age of 18.

Some of the parents compared the issue to the sexual development that they had when they were in high school, where nude photos were exchanged in locker rooms. The difference is in the permanence of sexting because of the ability to download and redistribute pictures.

Despite the prevalence of sexting, Miofsky found that the activity seemed to taper off as the students matured, possibly rendering moot any concern about it at the college level.

“In my groups, I had freshmen, sophomores, juniors and seniors,” said Miofsky. “It seemed that by the time they were seniors, they felt that this type of behavior was immature and they had grown out of it, so I’m not sure if college kids are engaging in it compared to the freshmen and sophomores that I found in my research.”

When a person turns 18, he or she becomes a consenting adult, instantly mitigating the consequences of further sexting activity. Additionally, around this age, individuals have typically become more familiar with what Miofsky refers to as, “the normative modes of intimacy and healthy relationships.”

“I think at this stage it’s important to realize that this is a reality of adolescent experience,” said Miofsky. “It’s a part of their psychosocial development and also a way for them to express their sexual identity. So whether or not you agree with it and whether or not it’s normative at this stage, it’s a reality.”

Nathan • May 3, 2016 at 9:02 pm

In the image provided, with the phone displaying a text message, you wrote “dosometbing.org” instead of “dosomething.org.”