Pulitzer Prize winner Art Spiegelman’s Maus is more than a graphic novel about the Holocaust; among other things, it is a story about the cartoonist himself and how he channeled his family history into art.

While Lakeland College students and faculty have become well acquainted with Spiegelman’s representation of himself in the novel (that is, a sarcastic mouse with a cigarette dangling from his mouth), they witnessed him in the flesh when he graced the Bradley Theater stage on Nov. 18.

Peter Sattler, professor of American literature, introduced Spiegelman. He spoke briefly about the cartoonist’s influence on his adolescent years.

“Maus was the kind of story I hadn’t seen in comics before,” said Sattler. “[Spiegelman is] a trailblazer on one hand and a historian on the other—he looks closely at how comics of the past were created and inspires newcomers.”

One could hear a pin drop as the full auditorium waited in anticipation of Spiegelman, and the audience erupted in applause when he joined Sattler on the stage.

Possibly inspired by Sattler’s diversion, Spiegelman kicked off his lecture by detailing how MAD magazine helped him decide to become a comic at a young age.

“I grew up with comics,” said Spiegelman. “I learned about philosophy from ‘Peanuts’ and about sex from contemplating the question of ‘Betty or Veronica?’”

Smoking an electronic cigarette and dropping the occasional expletive, Spiegelman took the audience on a chronological journey through the evolution of comics and discussed the importance of the art form.

“Comics echo the way the brain works. People think in iconographic images, not in holograms, and people think in bursts of language, not in paragraphs,” said Spiegelman.

Spiegelman concluded his “What the %@&*! Happened to Comics?” lecture by taking a few questions from the audience, and several people gave him a standing ovation as he exited the stage.

Senior English major Krissy Olson was under the impression Spiegelman would do a book signing due to the campus shop selling his work at the event, and she was disappointed when he did not stop for autographs or fan pictures.

Regardless of the disappointment, Olson found the lecture interesting.

“Even though I’m a Japanese comics fan, I still found his lecture very informational,” said Olson.

“Everyone who has talked to me or sent emails is expressing how mesmerizing Spiegelman’s presentation was,” said Nate Lowe, associate professor of writing.

“There is no other Art Spiegelman in the world—no one else who can speak about comics for 90 minutes with the same depth and complexity and first-hand experience.”

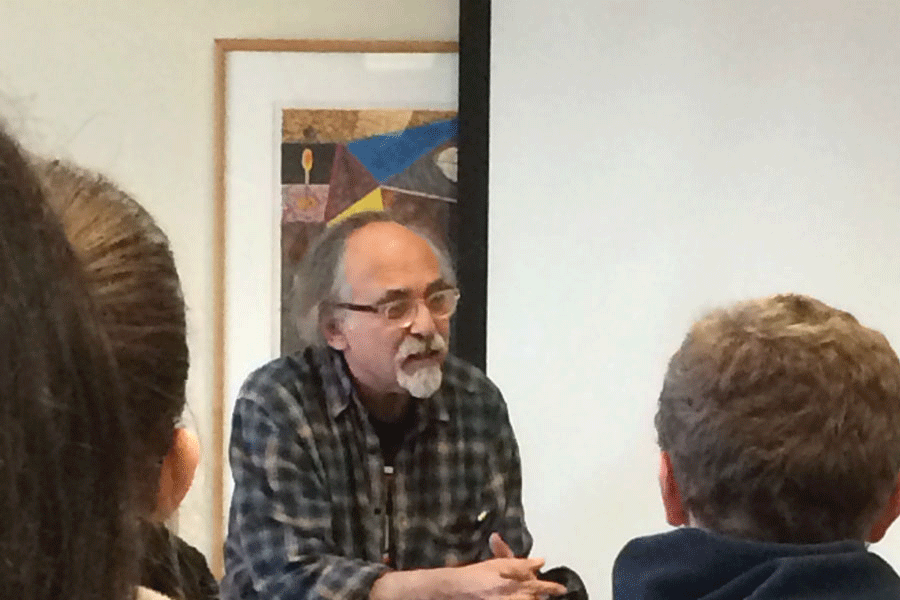

On Nov. 19, about 60 students were treated to a private question and answer session with Spiegelman.

Visibly tired from the events of the night before, Spiegelman propped himself up on the back of a chair and instructed, “If I fall over, just get the nurse.”

Some of the first questions Spiegelman received were in relation to what makes the comic medium unique.

“You’re allowed a very direct access into the cartoonist,” said Spiegelman. “Something very interesting to me about comics is the voice—the voice of the artist becomes literally visible.”

When asked if he would allow movies to be made of his comics, Spiegelman answered he is open to the idea with any comic except Maus.

“A studio with hoards of people would destroy [Maus],” said Spiegelman, “but if they want to make an animated version of ‘Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,’ they’ve got it!”

The conversation took a more personal turn when students began questioning how his battle with depression has influenced his work.

Spiegelman responded by saying that it made his parents put less pressure on him, which ultimately allowed him to pursue comics.

Additionally, his experiences with treatment facilities taught him “it was OK to be weird.”

Spiegelman also spoke briefly about his experiences making MetaMaus and detailed how the emotional calluses he developed during Maus had softened. It made him think about his family, and he sometimes wound up crying in the art room.

Since the majority of Maus focuses on the experiences of Spiegelman’s father, one of the final questions was whether or not the cartoonist regrets how he portrayed the man’s stubborn nature.

“Not anymore,” said Spiegelman before leaning in closer to the audience. “I wanted to present somebody with all his thorniness; it makes him more loveable because he is more like you.”