Addicted to addiction research

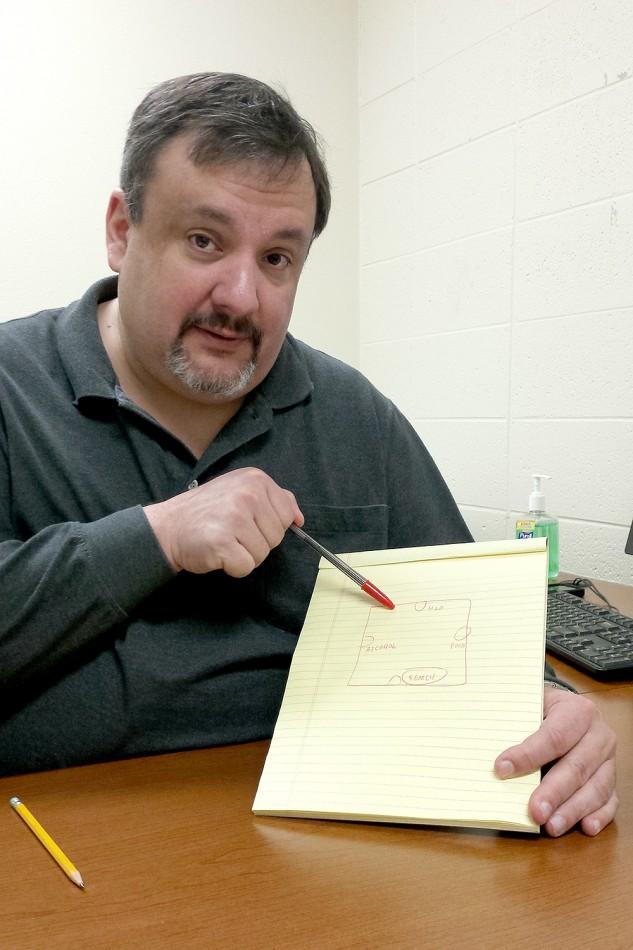

Anthony Liguori, associate professor of psychology, explains what the rat cage looked like in his experiment.

April 8, 2015

Within a rat cage, there are three levers that can be pulled that will open one of three slots on the remaining walls of the cage: food, water or alcohol. If a rat pulls the lever a certain amount of times, one of the walls will light up, and if the rat does not continue to search, then that wall’s designated substance comes out of the wall’s slot. The expense of the lever continually raises—at first it is only one pull, but eventually becomes thousands of pulls of the lever.

An individual would imagine that as the number of pulls increased then the rat would gradually only use it for what it needed and when it needed it. However, as the expense for the search rose to the thousands, the rats stopped eating the food and drinking the water. The rats began to use the search to only drink the alcohol.

This addiction research was Anthony Liguori’s, associate professor of psychology, dissertation. Liguori originally got involved in psychology because he believed himself to be a good listener.

Soon, he became very interested in behaviorism, which is learning and even possibly changing a person’s behavior through experiments, operant and classical conditioning and other psychological methods.

Liguori’s favorite studies that he did was his early work with alcohol because that was when he was first establishing his lab. At that time, he was involved in all aspects of the experiment because it was like “building a business from the ground up.”

In one study, he called the local police department to find their most knowledgeable police officer about drinking under the influence (DUI) cases. This officer taught Liguori that the best test when giving a sobriety test is asking the person to recite a chunk of the ABC’s (for example, from D to S). If that individual is in fact intoxicated, they will say letters out of order without realizing they made an error.

Another alcohol-related addiction study that Liguori and another psychologist conducted was seeing if individuals could identify their breath alcohol level. After the experiment, the participants were able to guess their blood alcohol level within 0.01.

“Across multiple time points, the actual blood alcohol level and their prediction were almost indistinguishable,” said Liguori.

A side project Liguori did between alcohol studies was a tanning addiction experiment. Another psychologist approached Liguori about the possibility of UV-ray light bulbs being addictive. In this experiment, they would allow the subjects to tan one time with one kind of bulb and then again with another.

The individuals in the study would come back each week to use “new bulbs,” but in reality, they were the same two bulbs as before: a regular light bulb and a UV-bulb. Just as an experiment with a drug and a placebo, the subjects of the experiment chose the “drug” (in this case, the UV-bulb), which proved that tanning can become very addictive.

Liguori’s first grant study involved testing the effects of marijuana on simulated driving. For the study, Liguori and his associates put an ad in the paper asking for non-dependent marijuana users to participate in the study.

In the study, they would be given a controlled amount of the drug before using a simulated driving system to determine if the subjects’ driving was altered or not.

While the experiment was going on, a local paper asked to cover the experiment in an article. By Friday, the story was the top story on “USA Today” for North Carolina. While watching Saturday Night Live (SNL) that Saturday, he had a premonition that the study would be featured on “The Weekend Update” of SNL, which it was.

“With the whole SNL thing, we had to be sure to control the public perception because we did not want to be seen as a marijuana vending machine because that’s not what we were doing,” said Liguori. “This was research.”

After the attention from SNL, an abundance of marijuana users called to be part of the study. Many of the individuals who called in response to the media exposure were heavily dependent on marijuana; therefore, they could not participate in the driving study.

However, Liguori saw an opportunity to do another experiment about marijuana withdrawal. Thus, Liguori had his second grant study about marijuana withdrawal using some of the individuals who called for the previous study.

Liguori has not done a study while at Lakeland yet. He and Elizabeth Stroot, professor of psychology, have been looking into conducting a study on the measurement of local addiction in the community.